Supplementary Material to the Uncollected Letters of Algernon Charles Swinburne, 3 vols. (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2005).

Introduction

At this site I correct a number of errors in my edition and especially take the opportunity to add new material, including a number of letters

from and to Swinburne. I am grateful to Catherine Trippett of Random House UK for

permission to post here Swinburne letters still under copyright.

Added too is an article, illustrated with photographs, about Swinburne’s funeral and

the controversy associated with it.

Especially helpful is an index to Appendix B (in vol. III, pp. 323-368). That appendix contains new material pertaining to 291

of Swinburne's letters published by Cecil Lang, The Swinburne Letters, 6 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959-1962): corrections, locations of

holographs, identifications, datings, and the like. The index will make those more

easily accessible.

I am grateful to John Walsh, editor of The Swinburne Project, for making these corrections

and additions possible. And I would be pleased to receive queries or further errata,

which I will add here from time to time.

One further note: all the material in my edition and here which is cited as being

in my possession is now at the Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library,

William and Mary. It should be cited now as being in the Sheila and Terry Meyers Collection of Swinburneiana.

Terry L. Meyers, Chancellor Professor of English, Emeritus

The College of William and Mary, in Virginia

The College of William and Mary, in Virginia

Addenda, Corrigenda, and Errata

The sections below separate what I regard as the more

important material from the less important.

The publication date of the edition is given as 2005 in

vol. 1, and sometimes 2004, sometimes 2005 in vol. II. In vol. III, I have

seen only 2004. All should be 2005, although the edition was actually published

in November 2004.

Terry L. Meyers, Chancellor Professor of English

The College of William and Mary in Virginia

The College of William and Mary in Virginia

March 2012

Vol I.—The More Important

- p. xv, note 1. I should clarify my anecdote about Swinburne Island. I thought at the time that the entire island (an artificial one) had been removed as an impediment to shipping. However, I had been misinformed; after being used to quarantine immigrants, the island had been abandoned and its buildings razed, but the island did and does still exist. It is not named, as I knew of course, after the poet (his father, Admiral Swinburne, does, however, John Mayfield told me, have a geographic feature named after him, in Canada, at the south tip of Prince of Wales Island [71°12'N 99°09'W]).

- p. xxi. To note 1 should be added:

The desire by the Commonwealth of Virginia to deter scholars from studying sexuality and Swinburne has an antecedent in England. In Forbidden Document (Leader Magazine, 20 May 1950, p. 10), Woodrow Wyatt, M.P., takes to task officials at the British Museum who refused permission to Randolph Hughes to read a number of letters and poems by Swinburne as well as Edmund Gosse’s An Essay (with Two Notes) on Swinburne (Letters, VI, 233-48). The matter was discussed in the House of Commons in April, May, and July 1950.

- Letter 18A. p. 11. To note 2 should be added:

An unrecorded glimpse of Swinburne at Oxford is afforded in an interview with one of his contemporaries, James Bryce (1838–1922). Bryce affirms that discussions in Old Mortality occurred over tea and toast (not all biographers have wanted to believe this) and recalls Swinburne as a student of brilliant gifts:Swinburne, who was a fascinating companion, with great social charm, has always seemed to me the most brilliant members [sic] of this group. In all he wrote, as well as in his talk, we discerned the genius that has since been so universally recognized. I remember a striking little poem he recited at one of our annual festivals, and can still recollect by heart his admirable parodies of what was then called the ‘spasmodic school of poets’ [see the poems by ‘Ernest Wheldrake’ in Swinburne’s purported review in Undergraduate Papers (February-March 1858), reprinted in New Writings by Swinburne, pp. 81-7]. He had been educated at Eton, but it was as much his own fondness for study as anything his school had done that gave him his wide knowledge of the Greek poets and mastery of Greek verse. He was also extraordinarily well read in French as well as in English literature, a fervent admirer of Victor Hugo, and, like pretty nearly all of us a no less fervent denouncer of Louis Napoleon, who was then Emperor in France.In a lengthy disquisition on Browning’s reputation at mid-century, Bryce adds thatIt was Swinburne who, by reading some of Browning’s poems to us at one of our meetings, I think in 1858, first introduced us to the work of that great poet. I recollect, as if it was yesterday, his reading aloud of The Statue and the Bust and The Heretic’s Tragedy, with, I think also, Bishop Blougram’s Apology.(“Our Need is Poets, Says James Bryce,” New York Times, 29 April 1907, p. 1) Gerald Monsman is skeptical that Swinburne read Bishop Blougram’s Apology to Old Mortality both because the poem is so long and because it is not recorded in the society’s Minute Book (“Old Mortality at Oxford,” Studies in Philology, 67 [1970], 367n).

- Letter 35A. p. 15. In note 1, Hallem should be Hallam

- Letter 35A. p. 15. In note 4, Crew

should be

Crewe

Add a note: See also my Swinburne’s Will Drew and Phil Crewe & Frank Fane: A Swinburne Enigma, The Book Collector, 56:1(Spring 2007), 31-34. -

Letter 70A p. 30. To note 1 should be added:

For more on Mary Gordon, her life and her work, see Jeremy Mitchell and Janet Powney, "A Forgotten Voice: Moral Guidance in the Novels of Mary Gordon (Mrs. Disney Leith), with a Bibliography," The Victorian [Online], 2.1 (2014): .

- Letter 121B. p. 64. In the last line of paragraph 3, “is charming” should be subscripted (and the previous line’s superscript should also be subscript)

- Letter 122B. p. 66. In note 1, Herfordshire should be Hertfordshire

- Letter 134A. p. 70. In ll. 14-15, /- should be closed up

-

Letter 148A. p. 76. To note 6 might be added this:

Several other recent discoveries bear on Swinburne’s literary career and fame.Richard Crawly’s satirical survey in 1868 of contemporary authors deals with Atalanta in Calydon and Poems and Ballads (See Horse and Foot, or Pilgrims to Parnassus [London:John Camden Hotten, 1868]).A poem by James Lindsay Gordon that seems to date from the 1890’s is dedicated to Swinburne; see “A Ballad of the Prince” in Ballads of the Sunlit Years (New York: North American Press, 1904). Gordon’s admiration of Swinburne and Rossetti, I like to think, might have developed from his studies at the College of William and Mary (see Armistead C. Gordon’s sketch in The Library of Southern Literature, ed. Edwin A. Anderson, et al., 17 vols. [Atlanta: Martin and Hoyt Co., 1909], V:1920).

- Letter 157A. p. 80. In the last line, imperfect. should be imperfect,

- Letter 192A. p. 100. In note 2 the women are should be that women are

- Letter 231B. p. 114. In note 3, Parnell should be Purnell

- Letter 275A. p. 133. In note 1, April should be February

- Letter 275A. p. 134. To note 2 should be added:

Alfred Rosling Bennett in his London and Londoners in the Eighteen Fifties and Sixties (NY: Adelphi, 1925) offers a description of Menken’s act not, I believe, generally known. Menken, says Bennett, had a good figure, and hid it not under a bushel, but I imagine that the scantiness of her raiment, then something to wonder at, would make no great sensation now. Every night, bound to the raging courser [“really,” he says, “a well-trained tamed steed”], she was galloped over the Steppes at Astley’s—the said Steppes being zig-zagging inclines amongst mountains—at about half a mile an hour, so that the horizon took a long time to reach and patrons had plenty of anatomy for their money (p. 339).Watts-Dunton reported a remark by Swinburne on Menken that appears not to have been much noticed. He mentioned in a letter to The Times that “some few years before his death I asked Mr. Swinburne what he thought of ‘Infelicia.’ His answer was, ‘Can you ask me? A girl may be admired as ‘Mazeppa’ without being admired as a poet. I think it the greatest rot ever published’” (“Swinburne’s Pamphlets,” The Times, 21 May 1909 p. 8a).

- Letter 309A. p. 164. Stoddard Martin is able to clarify Venturi’s allusion in this letter to what Swinburne had apparently described to her, “the Wagner affair,” “a screaming farce”: I am quite sure that it must be the news that broke in the summer of 1869 about the conductor of the Munich Opera, Hans von Bulow, and his finally agreeing to start divorce proceedings with his wife, the mother of his children, Cosima Liszt (daughter of Franz), who had been living off and on for three years with Wagner, by whom she had had a daughter and recently a son (Siegfried, eventual heir to directorship of the Bayreuth Festival and father of Wolfgang who just gave up same in 2009). What made this more of a sensation was that Bulow was Wagner's favoured conductor and had presided at great pains over first performances of Die Meistersinger in 1868 and was preparing that summer to conduct a command performance of the first part of the Ring for Ludwig II of Bavaria, their patron and paymaster. Ludwig, a covert homosexual, was horrified to learn that his favourite composer had been committing adultery with the wife of his court conductor, not least because the matter had carefully been kept hidden from him. Wagner had troubled his reign since 1865, when he had been banned from Munich by the Cabinet on the grounds that he was using the young king's devotion to his work to set himself up as an all-purpose advisor. The lid came off this boiling pot in the months preceding the exchange between Swinburne and Venturi, and Wagner's many enemies (and friends) were busy stirring it in the press, German, French, what have you.

- Letter 309A. p. 165. In line 12, Mr Holysake should be Mr Holyoake

- Letter 309A. p. 165. In note 9 Holyoke should be Holyoake

- Letter 319A. p. 169. In ll. 19-20, “apocryphal” should not be superscript

- An added letter:

321B.To: John Thomson (?)

Text: MS., Jerome McGann.

[November 1869?]The Argosy – Vol. 6 – was not received on Wednesday. The parcel directed to Lady J. Swinburne contained ‘Violet Douglas’ & ‘The Malay Archipelago’ Vol. 1st. Nothing else was sent but the comic papers, Fraser, & Templebar.[a flourish] - Letter 356C. p. 189. In line 9, honor should be honour

-

Letter 357A. p. 193. To note 7 should be

added:

To the secondary literature on Swinburne’s sexuality should be added an overlooked essay by Jill Forbes, “Why Did Swinburne Write Flagellation Poems?,” 1837-1901: Journal of the Loughborough Victorian Studies Group, no. 2 (October 1977), pp. 21-31.

-

Letter 375A. p. 191.

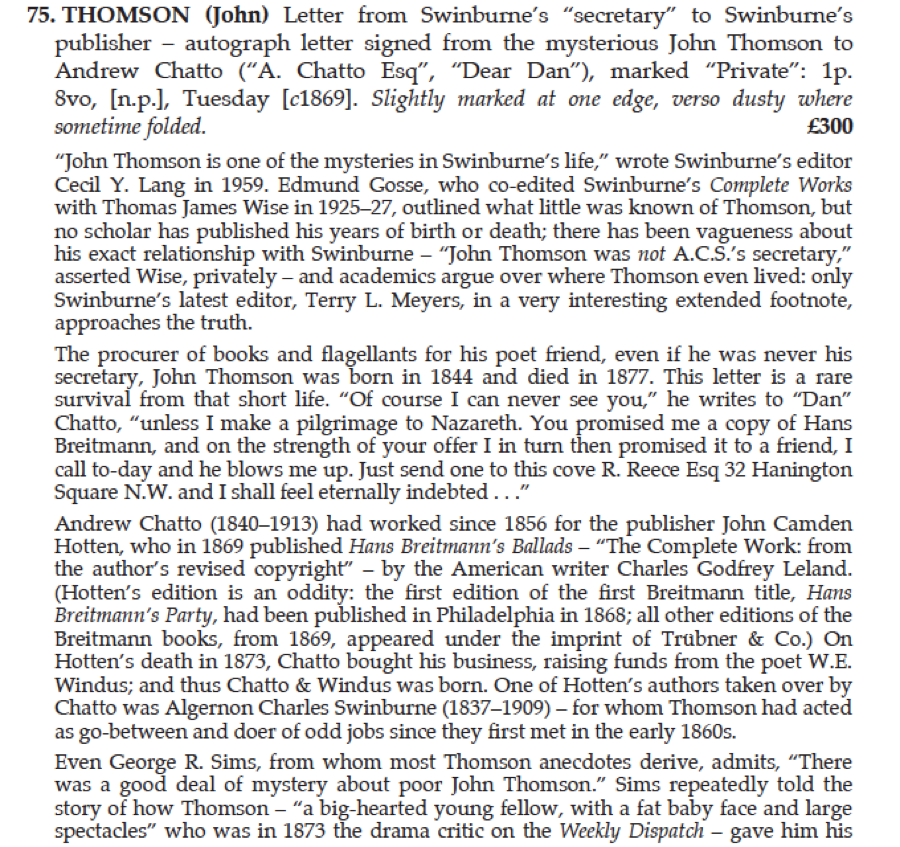

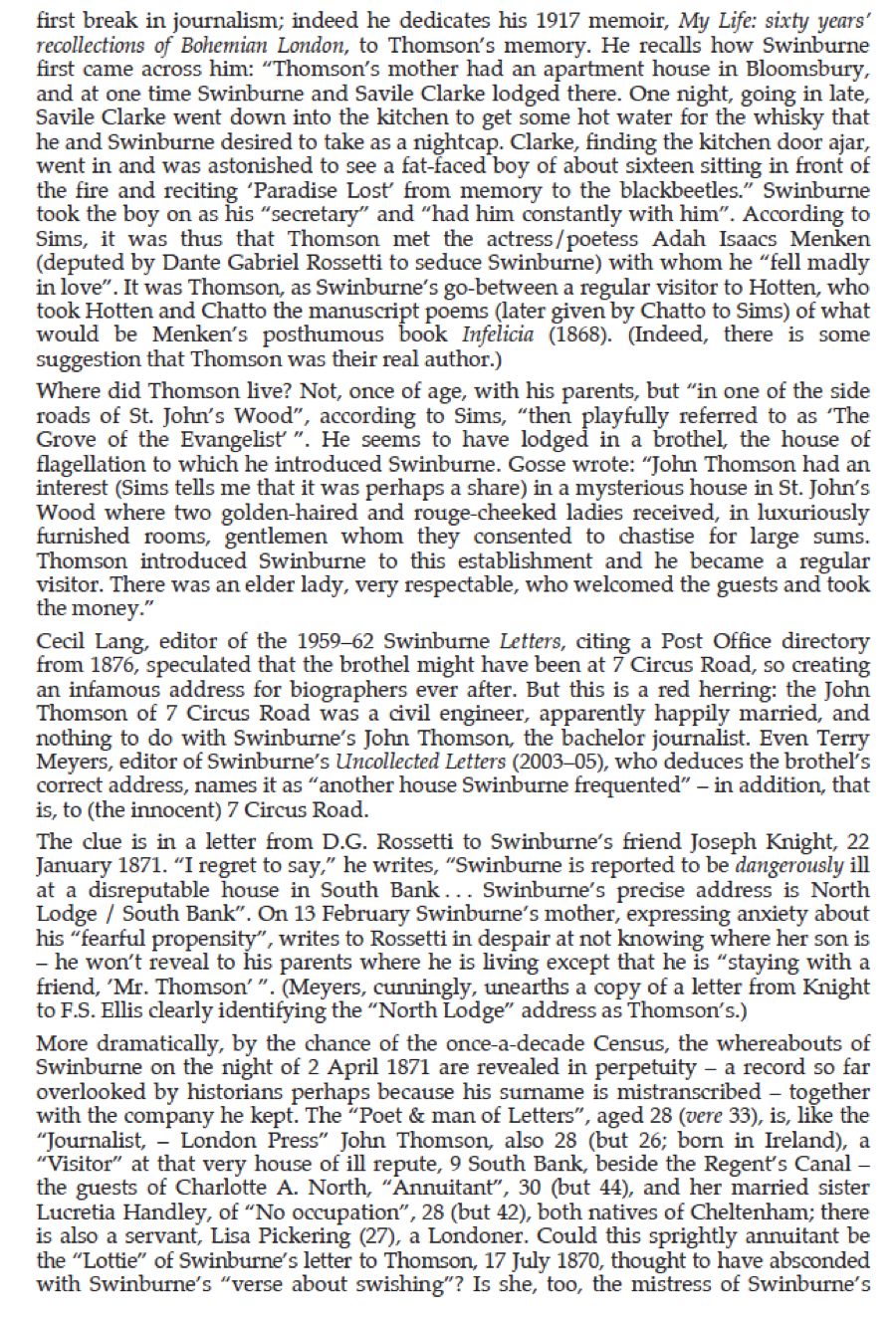

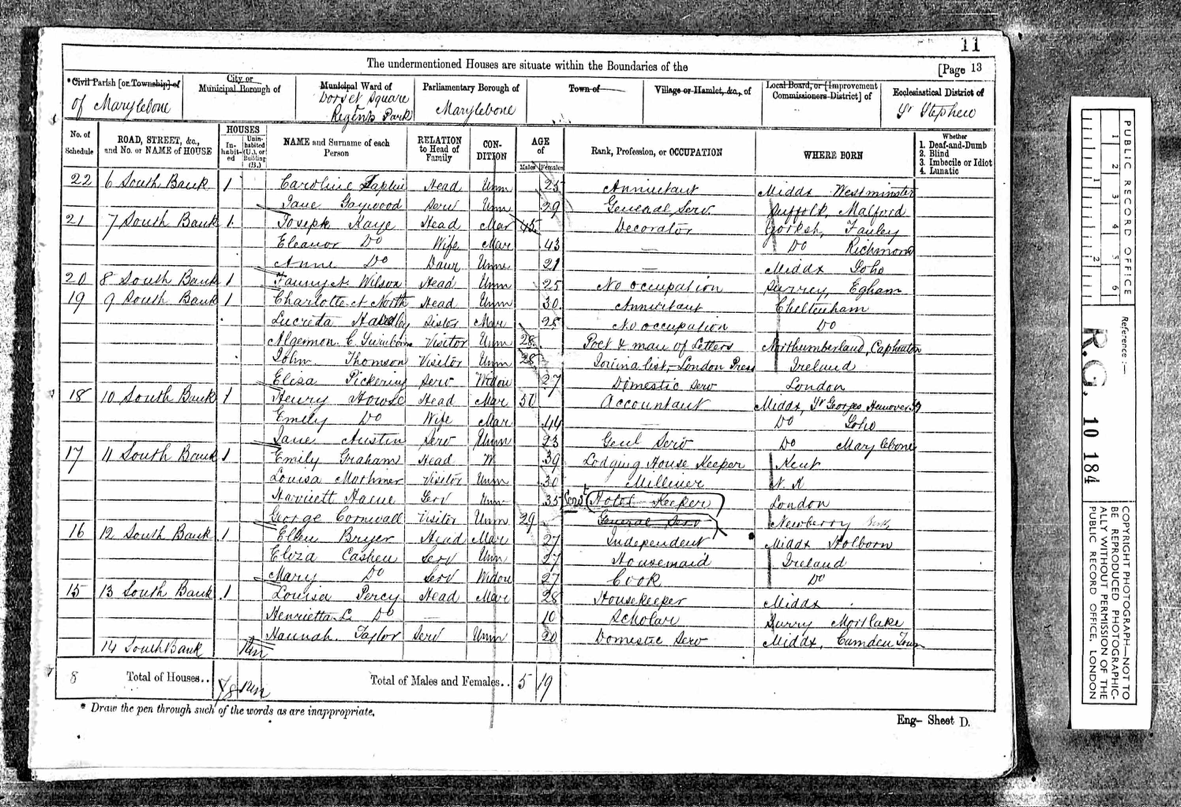

To note 1 should be added this material concerning John Thomson (and see too the note to Letter 275A), material developed by the English bookseller James Fergusson, material which he has generously allowed me to use even as he is working to develop further information on Thomson.Mr. Fergusson also sent me a scan of the 1871 census page (see below; used with permission from the National Archives) to which he refers in this description of an item offered in his catalogue Two Magpies: Letters & Papers from the Collections of Jonathan Gili, Christopher Lennox-Boyd & Others (Summer 2013).

Figure 2. Excerpt from James Fergusson's catalogue Two Magpies: Letters & Papers from the Collections of Jonathan Gili, Christopher Lennox-Boyd & Others (Summer 2013).

Figure 3. Page from the 1871 English census, featuring an entry for “Algernon C. Swinburne.” Used with permission of the National Archive.

- Letter 400A. p. 221. In line 2, favor should be favour

-

Letter 400A. p. 221. I should have been less skeptical of Swinburne’s attending a reading by Robert Buchanan, for I have found a previously unknown account by Will Williams (in 1875 editor of the London Magazine) that suggests Swinburne attended more than one: I shall never forget seeing him [Swinburne] at the poetic readings given by the poet Buchanan, some years ago, in the Hanover-Square Rooms. There, in a corner, his intellectual face now wearing a scowl, now a beatific expression, as he was pleased or displeased with his brother poet’s elocution, did he sit twirling his fingers and thumbs in a ludicrously excited way. Ere long he became the observed of every one. ‘Who is that?’ whispered a mercantile friend to me, nodding toward him. ‘That,’ replied I, wishing to surprise the man of figures, ‘is one of our greatest poets, Mr. Swinburne.’ ‘Indeed!’ was the reply, ‘Well, I’ve always heard that poets were a rum lot; now I’ve no doubt about it!’(quoted by the American editor and complier William Shepard [Walsh] [1854-1919] in Pen Pictures of Modern Authors [New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1882], pp. 205-206; Williams’ account first appeared in Appleton’s Journal, 21 August 1875, p. 252).Though wrong in some biographical details, Shepard recalls Swinburne’s manner and behavior and other details: “his voice is monotonous, he intones—but it is very earnest. Before the first series of his poems and ballads came out he kept them in a fire-proof box, in loose sheets, and plunging his arm in up to his elbow, used to bring out his favorites.” Shepard mentions that “Anactoria” was known in manuscript among Swinburne’s friends as “Sappho”: “we did not think that he would ever dare to publish this poem with ‘Dolores,’ ‘The Leper,’ etc.” (pp. 203-204).Shepard includes another anecdote Williams quotes from the London correspondent of a provincial newspaper. The correspondent recounts at some length Swinburne’s brilliant performance at a dinner hosted by a lady to whom the poet at the end of the evening inscribed a copy of his poems. Then three days later he reappeared and apologized, having no recollection of the evening and thinking he had missed it: “he had mislaid the card—he had mistaken the night—he had had to go down into the country.” Shepard also tells of Swinburne’s taking a footstool to a public banquet honoring Browning: “he insisted on placing [the footstool] at the master’s feet and solemnly seating himself thereon.” Browning is said to have “a warm liking for Swinburne,” but is also supposed to have cautioned him: “‘You foolish boy!’ he is represented as saying to him on one occasion, with a playful shake of the finger, ‘what do you mean by prostituting such splendid genius?’” Shepard concludes by quoting from the account of Swinburne by Louisa Chandler Moulton which she published in February 1878 in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine.

- Letter 419A. p. 231 In line 1, to you For should be to you. For

- Letter 422A. p. 233. In the second line of para 1, lend seems more likely to be send

- An added letter:

450A. To: Ford Madox Brown

Text: MS., South African National Gallery.

Holmwood,

Shiplake,

Henley on Thames.Dec. 14th [1872]My dear BrownAs it is first of all & most of all to your kindness & friendship that I owe the good fortune which has come to me I cannot but write at once to tell & thank you. Mr. Watts writes me word that Chapman & Hall offer <mo [?]> on most liberal terms to buy out Hotten, & having invested in my works to issue them in a cheap edition, such as theirs of Carlyle, which it will match. This Chapman expects to sell ‘by thousands’ & (says Watts) ‘will pay me for most liberally.’ It is the very thing & the very firm [?] I would have chosen.Even you never did a kinder thing for any of your friends than when you brought me acquainted with Watts. I wish I had any means of shewing my gratitude. Had it been Jowett instead of Dean Stanley whom Cambridge had complimented by a nomination as ‘select preacher’ (but they won’t do that in a hurry, J being in all Christian eyes the real ‘heresiarch’ & son of perdition, by the side of whose black infidelity the ‘rationalism’ of Stanley is white, or at least ma[u]ve[?]-colour) I might have a friend at court there which wd perhaps be of some service. As it is, I can only send my sincerest hopes that your election may prosper in that quarter--& remain in haste,Ever yours most sincerelyAC SwinburneAnd what a day of judgment & ‘the great jubilation’ it will be for British Virtue when I shall stalk triumphant over the land in a cheap edition sowing broadcast the seeds of immorality, atheism, & <illeg.> revolution! - An added letter:

490A. To: John Thomson

Text: Facsimile in Thomas Catling, My Life’s Pilgrimage (London, John Murray, 1911), p. [123].

Holmwood Nov. 25th [1873]Dear John,- The similitude of Shakespeare to the sea forms the overture of Victor Hugo’s book—“William Shakespeare”—pp 15, 16 (ed.1864).

- The license of using a singular verb <illeg.> after two substantives (as in the verses you quote) has always been admitted, I think, in modern English verse. Of course it is a license to say ‘the flower-dust & the flower-smell clings’ but even if unpardonable the offender will find himself chastised in good company.

Mille amitiés,Yours everA C Swinburne - Letter 524B. p. 319. Twice in the middle of the page, Checque should be Cheque

- An added letter:

535A. To: Ford Madox Brown

Text: MS., South African National Gallery.

The Orchard

Niton

Isle of WightJuly 17th [1874]My dear BrownI was very sorry to leave London without seeing you again if only to make my apologies, & express my regret for having been unable to attend either of your evenings, not being well enough at the time to go out to parties. I am very glad to hear that Hueffer’s projected book is to appear under Chatto’s auspices, & should be more so if I cd flatter myself with the hope that I might have been of any service in the matter.With regard to the adaptation of Bothwell to the stage, I had an interview by appointment with Watts the day before I left town, when I told him that he was fully authorized to make any arrangements with Mr. Oxenford in my name that he might think best. If on this understanding you, he, & Mr. O. can come to any conclusion, tant mieux. I don’t see, <that> having so thoroughly reliable a delegate, that my presence wd further or that my absence need impede a satisfactory settlement. I shall be here (Diabolo volente) for the next two months or so. It wd give me great pleasure to see myself on the boards & Mrs. Bell as my Queen; the only stipulation I told Watts I shd make as to the adaptation (in which he fully concurred) was that nothing shd be interpolated or retouched by any hand but mine; the adapter being of course free to use at his own fullest discretion the powers of excision & selection. The practical part of the business, as to division of profits &c, I leave of course in Watt’s hands with the fullest confidence.I have just read Quatrevingt Treize—it is simply a divine work, & your remarks on it exactly expressed my own present feelings. V. H. has written me a quite overwhelming note of thanks & praise for the dedicatory sonnet of Bothwell.When you see Forbes Robertson please tell him I only received this morning his note of the 6th inviting me to meet you at his house, which had I been in town I should have been delighted to do.Ever yoursAC Swinburne - Letter 562A. p. 330. In note 2, F. C. should be E. C.

Vol. II.—The More Important

-

An added letter:

563A. To: A. C. Swinburne, from Anne Benson Proctor

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

[mourning stationery]Oct 18th. 187432 Weymouth St.Portland Place WMy dear Mr SwinburneI find on again looking at your charming tribute to my dear husband that it ought to be dated the 4th instead of the 5th.I cannot tell you what a pleasure your good company was to me, how you lifted me out of all that has been pressed upon me for the last fortnight—With my Poet, all that was highest seemed to have gone—and left a woman whose whole time & thoughts were engaged by Lawyers, Rents, Lodgings &c—You said some words about taking up my time— had I not been obliged to go out, I should not have parted with you.—Your grateful old fd.Anne B. Procter

- Letter 598A. p. 9. To note 1 might be added:

To Swinburne’s attendance in the Reading Room of the British Museum, two further witnesses might be adduced, both in his later years. Laurence Binyon (1869-1943) recalled seeing Swinburne at work: … he had seen him once in the flesh. It was in the British Museum Reading Room, which Swinburne used to visit from time to time to consult the editions of the Elizabethan dramatists. There he would indulge in his gift of picturesque blasphemy and vituperation at the expense of the commentators of the play he was studying or at the expense of some neighbouring reader who was annoying him—and, being stone deaf, he imagined he was unheard. (“The Swinburne Centenary: Mr. Laurence Binyon’s Appreciation,” The Times, 5 May 1937, p. 14c) John Masefield (1878-1967) told a similar story: Then there [at the Reading Room] was that great figure Algernon Charles Swinburne. He was very deaf and was brought there by Mr. Watts-Dunton and set down at a table, while everyone in the room looked at him. Watts-Dunton shouted in a loud voice: ‘I will come back at one o’clock to take you out to lunch,’ and Swinburne then settled down to read. Being deaf he did not realize what an amount of noise he sometimes made, and from time to time indignant readers turned around to protest, but when they saw it was Mr. Swinburne they took no further notice. (“Mr. Masefield on His Early Reading,” The Times, 9 July 1936, p. 19g)

- Letter 634C. p. 24. The mention of Swinburne’s letter should have a note: See Letters, III, 34-35.

- Letter 663B. p. 30. The first sheet of writing paper is headed “Holmwood, / Shiplake, / Henley on Thames.”

- Letter 668B. p. 40. In line 1, checque should be cheque

- Letter 680A. p. 45. In line 2, ________ should be ____ _____

- Letter 685A. p. 52. In line 8, the two verticals should be immediately beneath the two c’s

- Letter 702A. p. 59. In note 5, [1877] should follow 1878

- Letter 709A. p. 65. The first three sentences of this letter, slightly reworked, appear in Pfeiffer’s Sonnets, ed. J. Edward Pfeiffer, (London: Field & Tuer, 1886), p. vi. Pfeiffer's Sonnets, ed. J. Edward Pfeiffer, (London: Field & Tuer, 1886). Retrieved from the HathiTrust Digital Library at

- Letter 830C. p. 112. In line 13, metaphyical should be metaphysical

- An added letter:

890B. To: Eugène Joël

Text: Printed in The Leicester Chronicle and the Leicestershire Mercury, December 15, 1877, p. 12.

3, Great James-street

Bedford-row

London, W.C.Monsieur, — Agréez mes remerciments bien sincères des beaux et puissants vers que vous avez bien voulu me dédier, et des paroles cordiales et sympathiques qui les accompagnent et que je n’ai reçues que ce soir même—c'est à dire quatre ou cinq jours “après date”—mais qui suffiraient presque à mêler un bon souvenir aux souvenirs exécrables de cette date maudite, le 2 Décembre lui-même.Algernon Ch. Swinburne.9 Décembre, 1877. - An added letter:

897A. To: William Michael Rossetti

Text: MS., South African National Gallery.

3 Gr Jas StJanry 17th [1878]Dear RossettiI trouble you with one line to beg one word ⁁by return of post in answer to the question whether in your edn of Shelley you had or had not a note on the ‘Numidian seps’ (Prom. Unbound, Act III, Sc.1) giving a reference to the passage in Lucan alluded to. There is no such note in Forman’s edn; & believing (what I now feel less sure of) that there was none in yours, my copy of which is at Holmwood, I have written to the Athenaeum announcing as my own the discovery of this rather eccentric & <illeg.> ⁁incongruous reference on the part of the Almighty tyrant. Let me know at once ⁁if I have wronged you, that my note may be withdrawn in time before next week.Ever yoursAC Swinburne - Letter 903C. p. 145. In note 1, 1877 should be 1878

- Letter 930A. p. 167. In line 9, [21] should be [’]

- An added letter:

980B. To: A Book Seller

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

The Pines,Putney Hill. S. W.Nov. 24th 1879SirI shall be obliged if you can send me the copy of Marvell’s Works marked in the accompanying leaf from your catalogue.I am, etc.A. C. Swinburne - Letter 1001B. p. 206. In line 4, favourite should be favorite

- Letter 1055A. p. 246. In note 2, Landon should be Landor

- Letter 1070B. p. 262. In line 3, honored should be honoured

- Letter 1070B. p. 262. In line 22, I must abhor should be I most abhor

- Letter 1081A. p. 265. In line 11, Carlyles’ should be Carlyle’s

- Letter 1096A. p. 274. In note 1, bottomless, should be bottomless.

-

Letter 1096A. p. 274. In the footnote, the

reference to “several versions” of Swinburne’s squib on Wilde might

have been more expansive:

In 1974 or 1975, John Mayfield directed my attention to two issues of the Foyles Bookshop magazine, Foylibra. In a review of The Trials of Oscar Wilde by H. Montgomery Hyde (August 1974, p. 35), Edgar Lustgarten quoted lines about Wilde that he understood were by T. W. H. Crosland:Earth to earthAnd sod to sodNo wonder the Almighty GodMade the pitBottomless.In the issue for November 1974 (p. 5), several correspondents linked the lines to Swinburne and offered variants. Gerald Hull thought the squib should read,When Oscar came to join his God,Not earth, but sod.It was for sinners such as thisHell was created bottomless.Jeremy Smith cited the lines as I quote them from the George Macbeth anthology of Victorian Verse and located them, attributed to Swinburne, in the Silver Treasury of Light Verse, edited by Oscar Williams (1957).My conviction that the squib is by Swinburne is based on its similarity in wit and homophobia to his squibs about John Addington Symonds (see note 1 to Letter 446A, above), but, as I said in CBEL3, “evidence is wanting.”

- An added letter:

1123A. To: Rev. Canon Frederick Langbridge

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

Dear SirThanks for the gift of your volume. I have taken measures to get your letter to Mr Morris duly forwarded to his present direction.I should not wish any one of my ‘Christmas Antipones’ to appear separately from the others; & <as> [?] I presume you would hardly wish to reprint the three as they stand.Yours very trulyAC Swinburne - An added letter:

1124C. To: Oswald John Simon

Text: George A. Yates, “The Centenary of Swinburne. An Oxford Letter. Persecution of Jews in Russia,” The Times, 10 April 1937, p. 15f.

The Pines,Putney Hill, S.W.January 31, 1882Dear Sir,I need not assure you of my cordial sympathy with your projected movement: but having no sort of connexion, direct or indirect, with the University which I left more than 20 years since without taking a degree, I think that my signature to an address intended for its Vice-Chancellor would scarcely be proper in itself and could certainly be of little or no service to a design which has no heartier well-wisher thanYours very truly,A. C. Swinburne - An added letter:

1155A. To: ?

Text: An Unidentified Auction Clipping, Terry L. Meyers.

The Pines,

Putney Hill.

S.W.July 12, 82.SirI am obliged to you for sending me the newspaper cutting just received from London, & remainYours trulyAC Swinburne - Letter 1195B. p. 313. Note 2 should be expanded: See too my review of Henderson, JEGP, 75 (July 1976), 456-8.

- An added letter:

1197A. To: T. Hall Caine

Text: T. Hall Caine, Cobwebs of Criticism: A Review of the First Reviewers of the ‘Lake,’ ‘Satanic,’ and ‘Cockney’ Schools (London: Elliot Stock, 1883), pp. 136n-137n. .

[November 1882?]The cruel injustice you have—of course unwittingly—done to the memory of Leigh Hunt is no matter of opinion; it is one of fact and evidence. So far from attempting no defence of Keats, in 1820 he published, on the appearance of the “Lamia and other Poems” in that year, perhaps the most cordial, generous and enthusiastic tribute of affectionate and ardent praise that had ever been offered by a poet to a poet, in the shape of a review almost overflowing the limits of the magazine in which it appeared (the Indicator ). A more “loud and earnest defence of Keats” could not be imagined or desired. And if Keats ever forgot this, or ever expressed doubts of Hunt's loyal and devoted regard, it simply shows that Keats was himself a disloyal and thankless man of genius, as utterly unworthy as he was utterly incapable of grateful, and unselfish, and manly friendship. - Letter 1241B pp. 349-350. To this letter might be added material in my collection

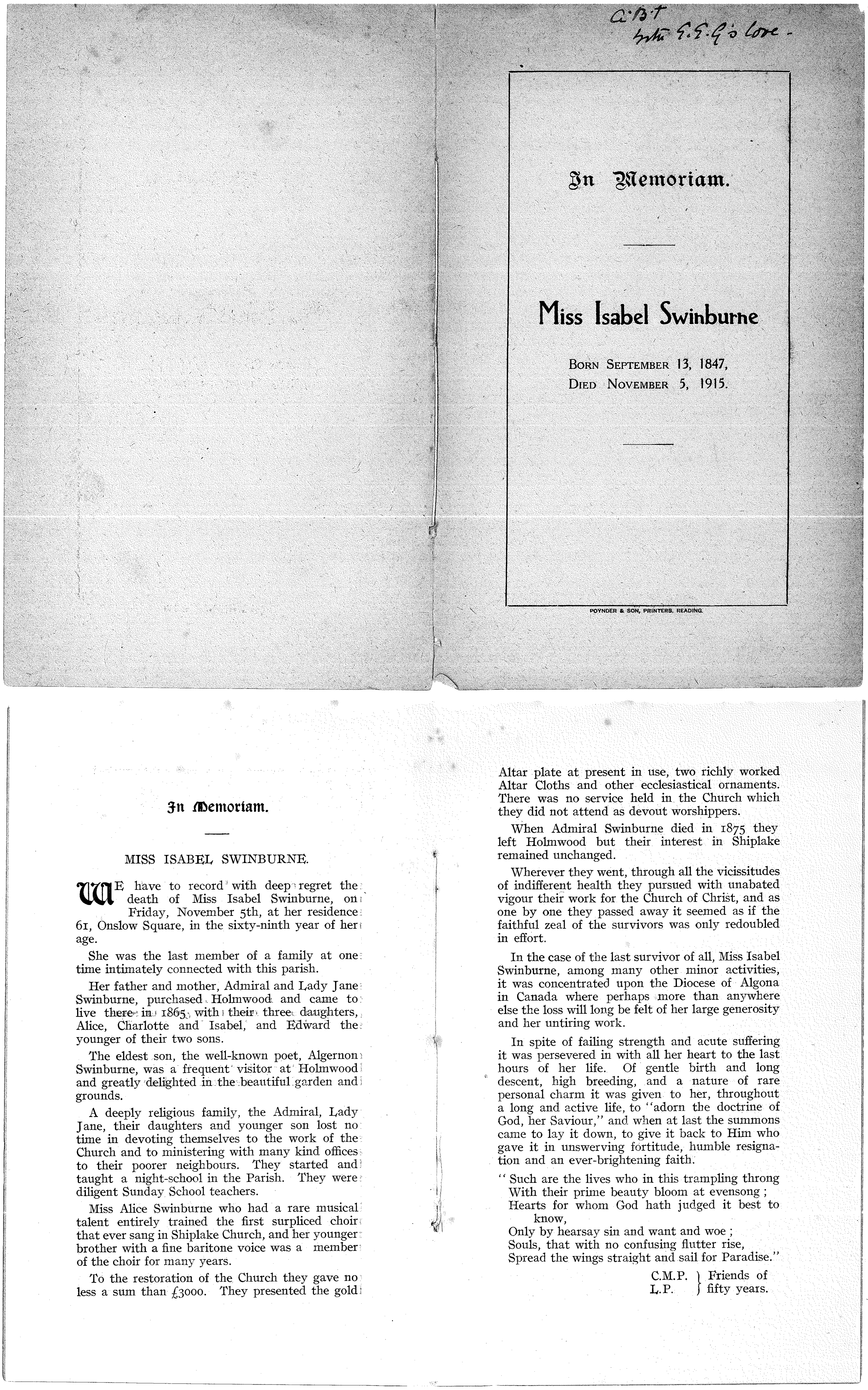

relating to Swinburne's sisters and brother, The picture is of Isabel Swinburne and

the memorial of her mentions the family piety.

Figure 4. Portrait of Isabel Swinburne.

Figure 5. A memorial for Isabel Swinburne. - Letter 1247A. p. 354. Swinburne’s allusion to his “parabasis” of Aristophanes’ “The Birds” should have a note: Published in The Athenaeum, 30 October 1880, collected in Studies in Song (1880).

- An added letter:

1301B. To: Lord Houghton

Text: Facsimile in an electronic “Occasional List,” September 13, 2013, Maggs Bros., Ltd.

The Pines.

Putney Hill,

S.W.[November 14, 1884]Dear Lord HoughtonVery sorry to hear of your accident. Watts & I will come to luncheon on Sunday with pleasure. He wrote yesterday to accept the invitation for Saturday, as we both thought that was the day named in your note.Ever yours truly,AC Swinburne - An added letter:

1322C.5. To A. C. Swinburne, from Mary Louisa Molesworth

Text: MS., The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin; printed in Terry L. Meyers, “Swinburne Shapes His Grand Passion: A Version by ‘Ashford Owen.’” Victorian Poetry 31:1 (Spring 1993), 113-117. Included here with permission.

85, Lexham GardensKensington, W.May 2nd [1885]My dear Mr. SwinburneI was in time for Miss Ogle —so my stupid mistake (not Yours) did no harm—Rather good! For I found Miss Ogle so “very, very, very anxious,” to see you, (she told me how to write the very’s) that she is staying a day later in town on purpose— Will you therefore come to luncheon on Tuesday—26th.—at 1.30? This is the day I have arranged with Miss Ogle— Please let me have one word by return to say you will come— You don’t know how glad I shall be to have been the means of procuring an hour or two’s talk together for you & your old friend—so you will come, won’t you? & my blundering will have been lucky— Miss Ogle told me to tell you she remembers everything—all the readings & consultations—she is working at her second novel now—& retaining your names—Yours most trulyLouisa Molesworth& “Mark”—the villain I think is one— - Letter 1407B. p. 423. In line 9, difficulty were about should be difficulty were absent

- Letter 1407D. p. 424. In the date, [1887] should be [1887?]

- An added letter:

1421A. To: Edward Swinburne

Text: MS., The Sheila and Terry Meyers Collection of Swinburneiana, the College of William and Mary

The Pines,May 16. 87My dear EdwardI return the papers at once with my signature duly appended. I am very much obliged to you, both for explaining the matter to me sufficiently & for not explaining it too much at the risk of addling my head with details.I always feel conscious of an incipient softening of the brain when anybody attempts to make me follow a calculation of any kind. Bertie rather self-complacently asked me the other day what I thought of rule-of-three. I could only intimate that I thought it a very nice game for boys who were strong enough to play at it—with or without wickets.Will you tell Ally I meant to have answered her letter yesterday & hope to do so today or tomorrow?With best love to allEver your affectionate brotherAC Swinburne -

An added letter:

1431A. TO: FRANK HARRIS

Text: “Fine Passages in Verse and Prose; Selected by Living Men of Letters. I.,” The Fortnightly Review, August 1, 1887, p. 316.

[July 21, 1887]I had naturally and inevitably to resign all thought of choosing any one or two or three passages from either Shakespeare or the Bible, and took it for granted that everybody would understand why. There are too many passages equally and diversely great and unsurpassable. Nor do I mean that there are not other passages in AEschylus or in Dante which may be set beside or above the two I have chosen — but simply that there are none in which I happen to take more pleasure.I know no translation of AEschylus or Dante which may not be described as ‘unspeakable’ for inadequacy — and certainly I should never dream of attempting a new version.AEschylus, Agamemnon, vv. 1035 — 1177, from “εἴσω κομίζου καὶ σύ· Κασσάνδραν λέγω,” to “τέρμα δ’ἀμηχανῶ.”Dante, Inferno, xxvi., 25 — 142, from “Quante il villan, ch’al poggio si riposa,” to "Infin che’l mar fu sopra noi richiuso.”

- Letter 1461A. p. 441. In line 1, “Mackail” deserves a note: J. W. Mackail (1859-1945), classicist and editor, the biographer of William Morris.

- Letter 1466B. p. 445.

In note 2, Daily Mail should be Daily NewsThe Daily News printed a public reply to Swinburne’s letters mentioned in this note: “Mr. Swinburne and the Daily News,” 29 March 1888.

- Letter 1480. p. 449. In line 18, authorize the publication should be authorise the publication

- Letter 1508D. p. 475. In note 1, a direct and more likely source for the quotations is Browning’s “Confessions,” ll. 35-36.

- Letter 1526B. p. 485. To this letter might be added a footnote, an unrelated account of the conversation (including an amusing French name, Browning, Tennyson, Shakespeare, Fletcher, Hugo) during a luncheon at the Pines with Wilson Barrett (1846-1904), manager, playwright, and, at that moment, perhaps the most famous actor in England, accompanied by, most likely, Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947), the poet and essayist who was at the time Barrett’s literary secretary. Swinburne is described (“about middle height, has auburn hair and blue eyes”) as is his speaking: “when he talked earnestly his eyes seemed filled with music.” As for his reading, it “has a very great charm, a weird chanting quality.” And in reading lines that may have especially affected him, “How sad that nought can win dear love / But loss of dear love—,” “he seemed then to forget all in the world but the poetry; his hand grew firm; his young face came out like the sun; his smile gathered to a great beam; and his eyes yearned away from the book with an ineffable tenderness” (“Mr. Swinburne at Home,” The Pall Mall Gazette, 20 November 1889).

Vol. III.—The More Important

- Letter 1540B. p. 12. In note 1, Trafalger should be Trafalgar

- An added letter:

1543A.5. To: Marion Harry Spielmann, from Walter Theodore Watts-Dunton

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

Northcourt,Newport,Isle of Wight.22 Aug ! / 90My dear Mr SpielmannI am staying here with Swinburne at <his> the house of his Aunt Lady Mary Gordon; but as soon as I get back next week I will suggest an appointment with you. My article in the rough will be then written & we will compare notes. I shall be seeing Lord Tennyson (who is at Aldworth) soonYours everTheodore WattsP. S. Swinburne sends you kind remembrances - Letter 1543C. p. 13. To note 2 should be added:

The soap referred to was no doubt Swinburne’s favorite, “Samphire Soap,” “which was extensively advertised by a quotation from ‘King Lear’”: “A. C. S. believed implicitly that it was highly charged with the active principle of ozone. He sensed the wave in its odour, and the suds in his bath were refreshing to him as the foam of the ocean” (Clara Watts-Dunton, The Home Life of Swinburne [London: A. M. Philpot, 1922], p. 106). William Black wrote in 1888 that “a great poet of our own day, who is passionately fond of the sea, and is also an excellent swimmer, declares that, if you are pent up in town or country, you have only to use samphire soap in order to induce the impression that you have just come in from breasting the breakers off the rocks of Alderney or Sark” (“A Day's Stalking,” Longman's Magazine, 13 [December 1888], p. 179).

- Letter 1552B. p. 21. In note 3, add: The review was reprinted in Contemporaries of Shakespeare, ed. Edmund Gosse and Thomas James Wise (London: William Heinemann, 1919); see Bonchurch, XII, 307-320.

- Letter 1556A. p. 33. To the mention of William Bell Scott in note 2 should be added that in a letter of 29 November 1892, the Scottish writer William Sharp (1855-1905) took note of Swinburne’s anger at Scott’s Autobiographical Notes (1892): “Swinburne is going to slate it unmercifully (and very foolishly) in the December Fortnightly [“The New Terror,” 1 December 1892]. I was dining at his house in Putney the other day: he was very excited over ‘The Monster’ to whom he has paid so many affectionate tributes in verse!” (See The William Sharp Archive. Ed. William F. Halloran. 1 June 2006 []). In a note to Sharp’s letter of 5 December 1892 to Watts-Dunton, Halloran suggests that Watts-Dunton had sent Sharp Swinburne’s manuscript or proofs for Sharp to use in writing his review of Autobiographical Notes (The Academy, 3 December 1892). I sketch the relations between Sharp and Swinburne in my The Sexual Tensions of William Sharp (New York: Peter Lang, 1996), pp. 59-62. Included there is Sharp's poem, To Mr. A. C. Swinburne.

- Letter 1556C. p. 23. The manuscript of this letter is now in the collection of Terry L. Meyers.

- An added letter:

1563A. To: Edwin Arnold

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

The PinesPutney HillSWJuly 8. 91Dear SirI have begun a short essay on English poetry of the lighter kind (suggested by the appearance of Mr. Locker-Lampson’s ‘Lyra Elegantiarum’ in an enlarged edition. I do not know when it will be ready for print, but if you should wish to have it for the Forum it is at your service when completed.Yours sincerelyAC SwinburneE. Arnold Esq. - An added letter:

1566A. To: Francis Warre Cornish

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

My dear SirI quite agree to your proposal & fully approve of what has been done with regard to my ode. I need not say it was not written with any afterthought of profit but simply as an offering of loyalty.In great hasteYours very trulyAC SwinburneJuly 30 [1891]

- Letter 1575A. p. 27. In line 3, honor should be honour

- Letter 1599A. p. 39. To the note should be added that discussion of who should succeed

Tennyson as Poet Laureate took place

even in the columns of the New York Times; see, for

example, Edmund Clarence Stedman’s endorsement of Swinburne in the issue

of 27 October 1895, p. 29: “with respect, then, to the morals of his

muse, … he has not written an ignoble line.”

In his Private Diaries (ed. Horace G. Hutchinson [New York: E. P. Dutton, 1922]), the well-connected civil servant Sir Algernon Edward West (1832-1921), private secretary to Gladstone from 1892, recorded some discussions of the Laureateship in his circle, even before Tennyson died. He recorded in July 1891, for example, that Balfour favored Swinburne as Tennyson's successor (p. 19), but that George Murray, then Gladstone’s private secretary, looked into Swinburne's suitability only to discover his never having repudiated Poems and Ballads (1866), his Notes on Poems and Reviews (1866)], and his 1867 “[‘Appeal to England’] against the execution of the Manchester Fenians; so I am afraid that his chances of the Laureateship are over.” Nevertheless, says West, “Swinburne, had he been possible, appeared to be the favorite, from the Prince of Wales downwards” (pp. 63, 64). Indeed, he says outright that “the Prince of Wales was in favour of Swinburne” (p. 65) and quotes a letter from the Prince, 27 October 1892, to that effect (p. 69).

- Letter 1599A. p. 39. To the mention in note 1 of Swinburne’s likely being offered the Laureateship after the death of Tennyson should be added this further story, by “E. B. I-M,” who in the Daily Telegraph (12 April 12 1909, p. 10c) recalled being a passenger on the same voyage as William Morris to and from Norway in July and August 1896: I was a fellow-traveler with William Morris on his last sea voyage, taken in the unhappily fruitless search for health in 1896. In the course of one of many delightful talks I had with him, he told me that Swinburne had been ‘sounded’ as to the acceptance of the Poet Laureateship, vacant by the death of Tennyson, and that Swinburne, though highly appreciating the implied honour, had declined because it was not consonant with ‘the fitness of things’ that the writer of regicide sonnets should be the official poet of a Court. Morris added that after Swinburne’s refusal he himself was also ‘sounded,’ and that he too felt bound to decline, because, as he said, ‘people choose to regard me, and to call me, a Socialist.’ Jeremy Mitchell tells me that “E.B.I-M” must surely have been Ernest Bruce Iwan-Muller (1853-1910), a journalist whose appointments included Editor Manchester Courier (1884-93), Assistant Editor Pall Mall Gazette (1893-96), and leader writer Daily Telegraph (1896-1910).

- Letter 1606B. p. 42. Dead Dr. Hake should be Dear Dr. Hake

- Letter 1612B. p. 44. In line 3, honor should be honour

-

Letter 1613A. p. 45. I overlooked Cecil Lang’s use of this number; my letter 1613A

should be numbered 1613C.

To Lang’s note to his letter 1613A, on the publication of “Music: An Ode,” might be added that the poem also appeared in The Times, December 23, 1892, p. 6d.

- Letter 1619A. p. 47. Jeremy Mitchell suggests that the chaffing letters exchanged by Swinburne and Mary Gordon Leith as if between schoolboys may have originated many years before, and cites a comment by Leith in The Boyhood of Algernon Charles Swinburne (p. 21): “I think it was the following autumn [i.e., in 1864] which he [Swinburne] spent in Cornwall. My parents and I were in Scotland and I received constant letters from him. Among a great deal that is comic and clever, but only intelligible to one who understands our jokes and ‘characters’ under which we delighted to write, are some charming and graphic descriptions.”

- Letter 1619C. p. 51. In note 1, Flight should be Fight

- Letter 1649B. p. 73. In note 3, of lord should be of lords

- Letter 1654A. p. 79. In note 1, the inscribed book was not AOP but SPP(1884); on the half-title Swinburne wrote, Mary A. B. Gordon from her affectionate nephew AC Swinburne Nov. 8th 1894. A photograph of the inscription appears in Miscellany 2006: Catalogue No. 123 (2006), issued by Ian Hodgkins & Co. Ltd., item 79.

- An added letter:

1694B. To: Walter Theodore Watts-Dunton

Text: An Unidentified Auction Clipping, Terry L. Meyers.

Barking HallAugust 7, '96My Dear Walter,I have read your note, & the letter which I return herewith, to my mother. She will not hear of her name being published, whether in the title or sub-title (I mean in a note to the text) of the poem, but does not so positively object to a note explaining that the verses were written for the birthday of the author’s mother. I must say I should have thought that the very densest of human skulls could not have misconstrued the opening words—‘Fourscore years & seven’—or failed to connect them with the closing phrase—‘She who here first drew the breath of life she gave me.’Ever affly yours,A. C. Swinburne

- Letter 1695A. p. 109. In l. 3, adapted should be adopted

- Letter 1713A. pp. 115-116. To note 1 might be added this: Cockerell later recalled a visit to The Pines at about this time during which he urged Swinburne to send to the museum at San Gimignano his “poem on San Gimignano” (the context [see The Times, 8 August 1938, p. 13g] alludes to an account of a visit Swinburne in 1903 [See Uncollected Letters, 1773C, on which, see below], but does not identify the poem with certainty; I suspect it may be “Relics” [PBII (1878)]): “He readily consented and I sent his transcript, with his accompanying letter, to the museum. They were duly acknowledged, and I learnt from a subsequent visitor that both documents were placed on exhibition” (“Swinburne and San Gimignano,” The Times, 17 August 1938, p. 11f).

- Letter 1717A. p. 116. This letter has been printed in José María Martínez Domingo, “Una Carta Inédita de Rubén Darío a Algernon Charles Swinburne.” Bulletin of Hispanic Studies [Glasgow University], 74:3, 279-92.

- An added letter:

1734 bis. To: Richard Dacre Archer-Hind

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers..

The PinesAug. 4. 98My dear SirIt can hardly be necessary for me to say how welcome you are to print any of my verses to which your contributors have done the honour of translating them. It would greatly interest me to read the version of ‘The Garden of Prosperpine’ in Greek elegiacs.Yours sincerelyA.C. SwinburneR. D. Archer-Hind Esq - An added letter:

1735 bis. To: Richard Dacre Archer-Hind

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers..

The PinesPutney HillS.W.Sept. 11. 98Dear SirI am heartily ashamed to be so late in thanking you for your great kindness in sending me a transcript of the exquisitely beautiful version you have done me the honour <of> to make of my ‘Garden of Proserpine’. I waited to do so till I had made a thorough study of it: & between the oppressive & enervating heat of these last weeks (more trying to me than any other sort of weather) & a number of other calls on my time & energies, it is, I am shocked to find, just over a month since I ought to have acknowledged the kindness shown me & the honour done me. Your Greek seems to me quite as musical—whatever you say to the contrary—as my English ⁁can possibly be considered: & the wonderful & subtle felicity of rendering repeatedly struck me with astonishment as well as delight. I wish I were scholar enough to make my praise & admiration on that score worth having: but I am not, I hope, quite incapable of appreciation as well as <of> gratitude.Yours very trulyAC Swinburne - An added letter:

1738A. To: ?

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

The Pines,Putney Hill,Dec. 29. 98Dear MadamYou are most welcome to the use of my poems about children—any and as many as you please.Yours very trulyAC Swinburne - An added letter:

1739B. To: William Clark Russell

Text: Printed in The Morning Post, January 20, 1899, p. 7.

The Pines, Putney-hill, S.W. Jan. 17. [1899]Dear Sir, — Your name is more than sufficient introduction to any Englishman and lover of the sea. I among many thousands such, have to thank you for hours of delight. I can only at present assure you of my cordial sympathy with your noble and patriotic enterprise on behalf of Mercantile Jack. The son of a sailor who served under Collingwood need add no further assurance of his sincerity. —Yours very gratefully,A. C. Swinburne - Letter 1743B. p. 151. In line 7, spins? should be spins?’

-

An added letter:

1745C. To: Alice Swinburne

Text: MS., The Sheila and Terry Meyers Collection of Swinburneiana, the College of William and Mary

[Mourning stationery]My dearest Ally,I am indeed thrilled by your Pickwickian address. I am sure you & Abba have taken every precaution against such mistakes of rooms as made Mr. P’s visit so memorable. I am glad you are out of town, anyhow, tho’ flies would make me cut my throat. The one thing that has tempered this exceptionally infernal summer to me has been their unusual absence at this time of year. It has been awful—for me—& is still, in the afternoon, usually.I am very sorry to hear of a man of ninety—a friend of yours—having an accident. It must be very upsetting for his grandson’s festivities on coming of age—not that I at that age should have enjoyed the ceremony, if I know or remember myself.If you want a real old inn you should go to Newhaven & see the rooms in which Louis Phillippe & family slept the night after they fled from the Tuileries. Rather a change, & rather small & fusty, but lovely in shape & furniture.I read Walter the bit in your letter about the modest request made to you on my account. I leave you to imagine his comments.I have just ⁁this minute finished correcting the proof of my forthcoming tragedy —so you will make allowance for epistolary brevity & stupidity. I don’t like not to acknowledge your dear old letter at onceI sent off this morning a congratulatory letter to Mun in answer to a note which she was so very kind as to send me announcing the advent of Maria’s baby on the very day of its gracious condescension to make its precious appearance. She says ‘he is too sweet for words, & very nice & big & well.’ It’s nothing to say that my mouth waters (though it does)—my whole soul & body yearn to kiss its feet. They don’t mind that.Best love to you both & kindest rems from ‘the others.’

Ever your mt aff brotherAC Swinburne - Letter 1769A. p. 193. In the signature, C. should be A.C.

- Letter 1773C. pp. 198-200.

My guess in note 9 as to the author of this account of a visit with Swinburne was wrong. “M.B.” is Mario Borsa (1870-1951), Italian critic and journalist, who was living in London at the time (see Letters, VI, 166). Borsa visited The Pines 20 March 1903, not 1902, as he misremembered; given this corrected date, 1773C should be located later in the volume.Borsa’s account in 1773C is a redacted version of one he printed in The English Stage of Today, trans. Selwyn Brinton (London: John Lane, 1908). Some of the material elided may have an interest, as, for example, his descriptions of:

- Swinburne’s study: “His study looks out upon a garden, embellished by a statuette from the hand of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The walls of the drawing-room, study, and dining-room are covered with memorials of the glorious pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood — pictures, portraits, designs, and sketches, by Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Morris, and Madox Brown. In his study there are also reproductions of some of Turner's Italian landscapes” (p. 203).

- Swinburne himself: “While he was again expressing to me his satisfaction at the remarks of the Minister Galimberti [see Letters, VI, 166 and Leith, pp. 97-98], and the pleasure he had experienced at finding himself still remembered in Italy, I contemplated him. Swinburne — whose lineaments are reproduced to perfection in the celebrated portrait by Watts — is short, slender, and fragile in appearance, with narrow, sloping shoulders. His physical frame is a quantité negligéable; the man's entire personality is concentrated in his head. A fine forehead, both wide and lofty, on either side of which falls a tuft of wavy, whitish hair tinged with red, an aquiline nose, a prominent chin beneath a sunken mouth, a scanty beard, white at the roots and reddish at the tip, and two large glowing, shining blue eyes — eyes full of youthful vitality. And he was even then sixty-three years of age! Who would have guessed it! Certainly no one from those eyes, any more than from his copious flow of living, palpitating speech” (pp. 203-204).

- Swinburne on listening to Mazzini: “‘I shall never forget the hours I passed with him. On these occasions I rarely spoke; I listened reverently to him. After having known Mazzini, I began to understand Christ and His Gospel’” (p. 204).

- a book by Mazzini dedicated to Swinburne: “‘Do you know, he had it bound for me himself!’ And he drew my attention to the beauty of the binding. He told me that he remained in correspondence with Mazzini and with Signora Venturi up to the last” (p. 205).

- Don Luigi Pecori’s being delighted at the English reception of Garibaldi: “‘When I related this to Mazzini, he immediately made a note of the canon's name in his pocket-book’” (p. 206).

- an auction at Brescia: “‘And I had no money! Stuff for which the National Gallery would have paid millions! (Wouldn't they, Theodore?’ —‘Yes, yes!’ said Mr. Watts-Dunton. ‘Now tell him about Florence.’)” (p. 206).

- Landor: “‘Look here !’ (He fetched a volume of Landor's works, and showed me the portrait on the first page). ‘Well?’ ‘A typical John Bull!’ was my remark. ‘Quite true! But I wish,’ added Swinburne, ‘that John Bull, like Landor, were a champion of every truly noble cause !’” (p. 206).

- the books Swinburne displayed: “With the admiration of all true pre-Raphaelites for ‘craftsmanship,’ he drew my attention to the elegance, solidity, and good taste of the bindings. He showed me a Boccaccio, two fine editions of the Negromante and the Suppositi of Ariosto, and a Bembo picked up for a few pence at Bristol” (p. 207); and, a bit further on, “‘Oh, do you know that book of Giambattista della Porta on the ‘Physiognomy of Man?’ (And taking it up he began to turn over its pages, showing me the illustrations.) ‘As you know, Della Porta claimed to have established, from certain physiological affinities, corresponding moral affinities between man and the lower animals. Rossetti believed in it. I think that is so funny! Look at this portrait of Pico della Mirandola. What an extraordinary expression! And the face of Cæsar Borgia here — the face of a born leader of men.’ At this point Mr. Watts-Dunton interrupted him with a smile to tell me that Swinburne was writing a tragedy on the subject of Cæsar Borgia” (pp. 207-208).

- Swinburne’s work on Cæsar Borgia: “He continued to talk to me while searching for the manuscript, and I gathered from his remarks that Swinburne had devoted much detailed historical research to this subject” (p. 208).

- Swinburne’s last words to Borsa on having spent two hours talking about “‘dear old Italy’”: “‘Thanks, thanks!’” (p. 209).

To Mario Borsa’s account of the disorderly library within The Pines might be added a further glimpse in the application by Thomas St. Edmund Hake (1845-1917) for a Civil List Pension from the Royal Literary Fund:The petition of the undersigned humbly sheweth: —That your Petitioners humbly submit for your gracious consideration the case of Thomas St. Edmund Hake, who resides at 38 Amerland Road, West Hill, Wandsworth, in the County of London, with the object of soliciting for him a place on the Civil list.That Thomas St. Edmund Hake is 71 years of age and is married, with a delicate wife and three children, aged respectively 21, 17, and 13 (the eldest child being a daughter who, owing to her mother’s ill-health, manages the housekeeping) entirely dependent upon him.That he is the eldest son of the late Dr. Gordon Hake, who was a first cousin of General Gordon and a famous Author and Poet.……………………………………………………………………That for the last eleven years of Algernon Charles Swinburne’s life, and for the last fourteen years of Theodore Watts Dunton’s life, he acted as their Secretary, and that for 38 years he was their most intimate friend. During his Secretaryship a pension of £250 was offered to Mr. Swinburne but courteously declined.That while acting as Secretary he devoted all his time and energy to the work before him from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day, receiving at first £100 a year, which after eight years was increased to £150 a year. He was therefore compelled to relinquish his own literary pursuits and career, though he was described by Watts Dunton in the Athenæum, 1895, as ‘a rising novelist’. Mr. James Douglas wrote in the ‘Star’, November 19th. 1915 : —‘The World will never know what Mr. Hake sacrificed during his long and affectionate devotion to his old friend. He was his slave, his willing slave. He might have won for himself fame as a novelist if he had not ungrudgingly given his whole life to the drudgery of absolutely unselfish self-immolation. Mr. Hake possessed the sweetest and gentlest and kindest of natures, and he never wearied. His capacity for toil was amazing. There was a time when The Pines was choked to the roof with all sorts of literary lumber. The only man who could find anything was Mr. Hake. I remember a room which was so hopelessly congested that there was barely space for two chairs. But Hake held every clue in his hands. I hope Mr. Hake will give us a stout volume of reminiscences. Nobody could tell the story of The Pines as he can tell it. He alone could play the Boswell to Swinburne and his old friend. What stories he could relate! The danger is that he may put off the task too long.’That he has no private income, and that his only temporary means of support is a legacy of £200 left to him by the late of Theodore Watts Dunton.(Hake, Thomas St Edmund. Thomas St Edmund Hake. 1845-1917. n.d. MS Archives of the Royal Literary Fund: Archives of the Royal Literary Fund 3019. World Microfilms. Nineteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 6 Feb. 2014. Document URL )And both of these glimpses might be supplemented by the account by Arthur Christopher Benson of his visit to The Pines, April 4, 1903 (p. 64): .Hake (with Arthur Compton-Rickett) did contribute to hagiographic accounts of those living at The Pines in The Letters of Algernon Charles Swinburne, with Some Personal Recollections (London: John Murray, 1918) and The Life and Letters of Theodore Watts-Dunton, 2 vols. (London: T. C. and E. C. Jack, 1916). - Letter 1773E. p. 203. To the note on “First Fault for the Hundredth Time” should be

added: In “He’s Catching it! Isn’t it Nuts: Algernon Charles Swinburne’s Eton Swishing

Play” (TLS, January 10, 2014, pp. 14-15), Peter Leggatt dates “First Fault for the Hundredth

Time” to Swinburne’s days at Eton; that dating is the premise for an elaborate analysis

of the work (see ).

But even without seeing the handwriting, I am confident “First Fault” is one of Swinburne’s later fantasies about schoolboy flagellation. Its premise, a punishment for whispering in church, may have come to Swinburne as he wrote, January 14 [1879], his response to a poem by Mary Gordon Leith, “The Whistle in Church” (see Uncollected Letters, II, 162). He mentions “First Fault” in a letter of June 7, 1906 in a way that suggests the work is one that she had possessed (see Uncollected Letters, II, 275).

- Letter 1774D. p. 211. To note 1, mentioning a June 1906 production of Atalanta in Calydon, might be added a review in The Times, “Performance of Mr. Swinburne’s ‘Atalanta in Calydon,’” 8 June 1906, p. 7f. The review suggests some timidity in the redaction, avoiding the word “God,” for example, perhaps because the several performances mentioned at the Crystal Palace were “in aid of the Church of England Society for Waifs and Strays.” One of the Society’s orphanages, for girls, was located in Wimbledon, not far from Putney. A subsequent performance at the Scala Theatre was to benefit “the Bedford College for Women site and building scheme.”

- Letter 1774H. p. 217. This letter was drafted for the signers by Arthur Symons, according to Karl Beckson and John M. Munro, who include it in their edition of Arthur Symons: Selected Letters (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1989), p. 166.

- Letter 1807F. p. 246. In line 21, ‘Ginerva’ should be ‘Ginevra’

- Letter 1819A. p. 263. To note 1 should be added:

A largely unconvincing account of life at The Pines (The Sunday Times, April 11, 1909; p. 7f) claims that the marriage of Watts-Dunton “made no difference to the domestic companionship of the two men” and that “it was her [Clara Watts-Dunton’s] habit to visit The Pines every day to minister to the creature comforts of the poet and the critic.”

- Letter 1827E. p. 276. In line 2, honor should be honour

- An added letter:

1863D. To: Lucy Margaret Lamont

Text: MS., Terry L. Meyers.

The Pines,11, Putney Hill,S.W.March 29. 9Dear MadamYou are welcome to the use of my verses. The publishers, to whom I usually leave all such matters, will raise no objections when I do not.Yours sincerelyAC Swinburne - Letter 1861B. p. 299. To this letter might be added a footnote, an unrelated account via Watts-Dunton of Christmas 1908 at The Pines—Swinburne’s reading Dickens, his never having been in better health, and his habitual walk of “two or three hours daily, and there is hardly a child he meets on his way that he does not stop to give pence to and talk to.” Swinburne comments, according to Watts-Dunton, on the efforts by suffragettes in the preceding weeks to draw attention to their cause (e.g., their intrusion into the House of Commons and interruption of David Lloyd George at the Albert Hall): “‘they have recently shown that they are quite unfitted for the exercise of the vote. Theoretically women should be entitled to vote. We all are children of the same mother, Nature, and should be treated equally, but in practice I am afraid that the thing is wholly impossible’” (“Swinburne’s Christmas,” The New York Times, 27 December 1908, p. 2c).

- Letter 1863G. pp. 305-306. A note to the lines by William Michael Rossetti should

be added:

Part of this passage appears in Roger W. Peattie, “Swinburne’s Funeral,” Notes and Queries, 21 (December 1974), 467. Peattie identifies the document as a letter from Rossetti to William Holman Hunt.To Peattie’s account of Swinburne’s funeral and to Rooksby’s photograph of the service (see below) and account by Helen Rossetti (Rooksby, A. C. Swinburne, pp. 284-286) might be added a series of photographs published by contemporary periodicals as well as further information I've compiled. See my article Some Notes Relating to Swinburne's Funeral.

- An added letter:

1899.To: ?

Text: The Daily Telegraph, 12 April 1909, p. 10c.

I am not a professional or official poet, and could not undertake to write any verse—patriotic or other—to order.Yours very truly,A. C. Swinburne - p. [317]. l. 5 Rev.? should be Rev

- Letter 98. p. 326. Lytton-Bulwer should be Bulwer-Lytton

- Letter 291. p. 333. Tyrwitt should be Tyrwhitt

- Letter 1752. p. 366. A note should be added: The letter is reproduced in facsimile in John S. Mayfield, “Swinburne and the Agnostic,” Swinburneiana : A Gallimaufry of Bits and Pieces about Algernon Charles Swinburne (Gaithersburg MD: The Waring Press, 1974), p. 19. Mayfield’s note elaborates on the recipient and on an earlier printing of the letter (p. 179).

- In Appendix B, in addition, I should have called attention to Anna Unsworth’s comment on Letter 1857 in Letters (28 September 1908): “Swinburne on Mrs Gaskell.” Notes and Queries, 38 (236):3(September 1991), 323-24.

An Index to Appendix B

- Academy. 350, 362, 365

- Angus, W. C. 352

- Arnold, E. 359

- Arnold, M. 331, 332, 350, 353, 354

- Athenaeum. 347

- Benson. A. C. 366

- Black, W. 349, 360

- Blakeney, E. H. 366

- Blind, M. 336

- Boker, G. 337

- Boyd, A. 325

- Brown, A. W. 347

- Brown, J. 368

- Browning, R. 324

- Buisson, B. 351

- Bullen, A. H. 358, 368

- Bulwer-Lytton. 326

- Burne-Jones, E. 324, 334, 344, 354, 355

- Burton, R. 336, 347

- Butler, Josephine. 326

- Cambridge Union. 329

- Cannibal Club. 336

- Chapman, G. R. 327

- Chatto, A. 348, 349, 351, 352, 353, 357, 360

- Chivers, T. H. 358

- Cockerell, S. 364, 367

- Coleridge, E. H. 357, 365, 366

- Coleridge, S. T. 365, 368

- Collingwood, J. F. 331

- Collins, J. C. 346

- Colvin, S. 340

- Conway, M. D. 328

- Cook, E. T. 368

- Corelli, M. 355

- Cornish, F. W. 361

- Cornwall, B. 333

- Cotton, J. S. 362

- Craik, D. M. 351

- Crosbie, H. W. 323

- Crosskey, H. W. 323

- Daily Graphic. 361

- Dante. 332

- Davidson, J. 348

- Davidson, J. M. 357

- de Sade. 338

- de Saint Victor, P. 339

- Dowden, E. 358, 359

- Downes, R. P. 368

- Dryden-Mundy, P. 366

- Echo de Paris. 365

- Examiner. 341

- Farrell, E. I. 366

- Fiedler, H. G. 366

- Forman, H. B. 339, 349, 351, 353, 354

- Friswell, J. H. 331

- Goethe. 368

- Gosse, E. 344, 346, 347, 350, 352, 354, 355, 356, 358, 362, 363, 365

- Graham, L. 330

- Graves, C. L. 360

- Grosart, A. B. 365

- Halliwell-Phillipps, J. O. 349

- Hake, T. S.E. 367

- Harrison, E. 361

- Hatch, E. 323

- Haweis, H. R. 335

- Hayne, P. H. 346, 347, 348

- Hedda Gabbler. 363

- Herkless, M. K. 366

- Horne, R. H. 353

- Hotten, J. C. 328, 332, 340

- Houghton, Lord. 323, 324, 326, 349

- Howell, G. A. 331

- Hugo. V. 323, 330, 333, 334, 335, 339, 341, 342, 354, 356

- Ibsen. 363

- Inchbold, J. W. 359

- Ingram, J. H. 367

- Jackson, W. 365

- Jameson, F. 326

- Jourde, F. 349

- Journal des Débats. 365

- Joyce, T. H. 361

- Kirkup, S. 324, 332

- Knight, J. 327, 338, 343, 344

- Knowles, J. 364

- Landor. W. S. 346, 363

- Lee, S. 360

- Lippincott, F. 337

- Locker Lampson, F. 339

- Low, S. 360

- Lytton, Lord. 328

- MacColl, N. 346, 347

- MacLehose, J. 361

- Marston, P. B. 330, 338, 342, 351

- Mayfield, J. S. 339

- Mazzini, G. 346

- Milnes, R. See Lord Houghton.

- Minto, W. 362

- Morley, J. 333, 335, 336, 339, 340, 341, 342, 343, 344, 345, 350, 351, 352, 353, 357

- Morris, W. 344, 354, 363, 364

- Motherwell. 336

- Moulton, L. C. 347

- Myers, F. W. H. 364

- Nesbitt, E. 359

- Nichol, J. 323, 330, 342, 345, 346, 352, 356, 361, 362

- Pall Mall Gazette. 368

- Parnell, C. S. 360

- Parsons, J. R. 326

- Payne, J. B. 343

- Peacock, T. L. 351

- Périé, R. 343

- Poel, W. 362

- Powell, G. 330, 332, 339

- Proctor, Mrs. 332

- Punch. 358

- Redway, G. 357

- Reid, W. W. 361

- Rice, S. S. 344

- Rossetti, C. 357

- Rossetti, G. B. 367

- Rossetti, D. G. 334, 336, 337, 338, 339, 367

- Rossetti, W. M. 327, 329, 333, 336, 347, 349, 354, 355, 356, 357, 358, 366, 367

- Royal Literary Fund, Council. 365

- Ruskin, J. 326, 328

- Rutherford, M. See W. H. White

- Saffi, A. 336

- St. James's Gazette. 359, 360

- St. John Tyrwhitt, R. 333

- Salaman, C. K. 368

- Scott, W. B. 325, 352, 362

- Shakespeare. 368

- Sheppard, R. H. 357

- Shelley, P. B. 333, 358, 340

- Shields, F. J. 356

- Shorter, C. K. 363, 366

- Solomon, S. 333, 334, 338

- Spectator. 341, 350, 356

- Stedman, E. C. 341, 343, 355

- Stephen, K. 365

- Stoddard, R. H. 329, 337

- Strozzi, Ercole. 356

- Swinburne, Admiral. 337

- Swinburne, A. C.

- Satirical views of. 337, 358

- Sexuality. 325, 326, 337

- Works.

- Age and Song: To Barry Cornwall, 333

- Bothwell, 342

- Chastelard, 325

- fragments related to a family joke, 319-320

- Laugh and Lie Down, 346

- Memorial Verses on the Death of William Bell Scott, 362

- Temple of Janus, 323

- Unhappy Revenge, 346

- A Year's Letters (Love's Cross Currents), 337

- Swinburne, I. 355

- Swinburne, Lady. 336, 363

- Taylor, B. 329, 337

- Taylor, H. 353, 355, 356

- Tennyson, Lady. 362

- Thomas, F. D. 357

- Thomson, J. 333

- Times. 365

- Trevelyan, Lady. 325, 326

- Tytler, S. 351

- Vacquarie, A. 349

- Watts-Dunton, W. T. 340, 342, 343, 344, 345, 346, 348, 358, 360, 361, 362, 364, 365

- Waugh, F. G. 340

- Wheeler, S. 365

- Whistler, J. M. 326

- White, W. H. 365

- Winter, H. E. 348

- Wright, T. 367

Appendix B

- Letter 197. p. 330. Gentlemen’s should be Gentleman’s

- Letter 310A. p. 333. The English Vice should be expanded to The English Vice (London: Duckworth, 1978).

- Letter 475. p. 340. J. C. should be John Camden

- Letter 1140. p. 354. TOL should be TOLOP

- Letter 1605. p. 362. william should be William

- Letter 1767. p. 366. her should be for her

-

The following entries should be added:

- 20. To Lady Jane Henrietta Swinburne [February 22] 1860 (Letters, I, 30)

In 2008 Bonhams sold five letters from Sir John Franklin to Captain Swinburne, Swinburne’s father and, at the time, 1832, Franklin’s second in command. The description of the lot (#156, Auction 16202; June 24, 2008; ) notes that Captain Swinburne’s connection to Sir John Franklin might have had a bearing on Swinburne’s composition in 1860 of “The Death of Sir John Franklin“; it also suggests that Swinburne’s nickname, Hadji, might have reflected his father’s bemused recollection of his and Franklin’s negotiations with Hadji Pietro, the head of an irregular army seeking to be cut in on duties on currants as the newly independent Greece sought them as well. Both suggestions seem plausible. - 492. To Theodore Watts December 1, 1873 (Letters, II, 260)

Francis J. Sypher has elaborated Cecil Lang’s note regarding a lost article on Swinburne by the American journalist Olive Harper (Helen Burrell D’Apery [1843-1915]) in 1873.Sypher very kindly sent me a copy of his privately printed Swinburne & Olive Harper: The American ‘Interview’ from 1873 (New York: 2012) where he explores the circumstances surrounding Harper’s account of meeting Swinburne as published in a number of newspapers in America and even in Australia. Sypher’s booklet reprints the version that he tracked down in the Cincinnati Commercial (July 21, 1873, p. 2), “London Literary Nobs.” Although Sypher explores the several reasons to question whether the encounter occurred, he and I both tend to believe it did. As Sypher says, “it is not impossible that [Harper] could have met” Swinburne between the middle of May and June 5, 1873:Swinburne I have met also. Somehow, he does not strike me pleasantly. He is, I think, fearfully ugly, and has nervousness about him that makes you wish he would keep still just one moment. Swinburne lives with his father, a short distance out of town. Every now and then he escapes from rigid parental authority, takes a run up to London, and has what he calls a time. We in California would call it a ‘spree.’ But he seems to have the kindest feelings for his fellow men.To see this famous poet (Swinburne) [sic] write is a terrible experience. He took a sudden inspiration in my room one day, and, without a word of explanation or apology, seated himself at my writing table, displaced all my things, and commenced writing. His whole face worked vehemently; he pounded steadily with his left hand on the table, and his feet kept time in unison with his body to the monotonous thumping. As soon as he had finished, he jumped up, seized his hat, and with a hurried ‘good-bye,’ rushed off to find his friend Watts, to whom

- 1313. To Andrew Chatto February 15, 1885 (Letters, V, 99)

The copy of Passages in the Early Military Life of General George T. Napier, ed. W. C. E. Napier (London: John Murray, 1884), which Swinburne requested of Andrew Chatto was for a birthday gift for Bertie Mason, whose eleventh birthday was February 4, 1885. The volume is now in my collection and is inscribed “Herbert Walter Mason / from his affectionate friend / Algernon Charles Swinburne / February, 1885.” - 1418. To the Editor of The Times May 3 [1887] (Letters, V, 188-190)

This letter was reprinted in The Birmingham Daily Post, 7 May 1887. - 1646. To Edmund Gosse June 29 [1894]

(Letters, VI, 69)

This letter had been printed in part in The New York Times, 17 July 1894, p. 5. - 1784. To Mario Borsa March 18, 1902 [sic for 1903] (Letters, VI, 166)

Most of this letter was printed in Borsa’s The English Stage of Today, trans. Selwyn Brinton (London: John Lane, 1908), p. 202.

- 20. To Lady Jane Henrietta Swinburne [February 22] 1860 (Letters, I, 30)

Vol I.—The Less Important

- To the “Short Titles of Works Cited” (pp. xi-xiii) should be added:

, Pre-Raphaelite Twilight: The Story of Charles Augustus Howell (St. Clair Shores, MI: Scholarly Press, 1971) Pre-Raphaelite Twilight - p. xii. l. 23. Rooksby should be Rooksby

- P. xv, note 2. The title of the anthology edited by Jerome McGann and Charles L. Sligh is Algernon Charles Swinburne: Major Poems and Selected Prose.

- p. xv. In l. 3, wife Edith should be wife, Edith,

- p. xxiv. l. 1. Cirlce should be Circle

- Letter 13A. p. 6. In the date, September 10 should be 10 September

- Letter 16C. p. 10. In the address, Capheaton should moved to just above the date

- Letter 90C. p. 50. In note2, , see should be (see

- Letter 129A. p. 68. Delete note 1 as redundant

- Letter 134B. p. 71. In the head note, charles should be Charles

- Letter 143A. p. 75. In note 3, delete Algernon Charles Swinburne

- Letter 186C. p. 98. In note 2, delete Algernon Charles Swinburne

- Letter 221A. p. 110. In note 2, delete (Algernon Charles Swinburne, Bothwell: A Tragedy (London: Chatto and Windus, 1874))

- Letter 244A. p. 117. The figures should be aligned more squarely

- Letter 309A. p. 165. In line 7, [”]Our should be [“]Our

- Letter 337C. p. 178. In the text note, the should be The

- Letter 356C. p. 190. In note 1, Henley should be Henley

- Letter 371B. p. 206. In note 1, [21 September 1870] should be 21 September [1870]

- Letter 388A. p. 214. In l. 2, Twilight[“] should be Twilight[”]

- Letter 394B. p. 218. In note 1, Reminiscences should be Reminiscences,

- Letter 396A. p. 218. In the head note, [?] should be (?)

- Letter 430C. p. 242. The”Wshing” figures, shillings and pence, should be so aligned

- Letter 453A. p. 262. There’s a mistaken blank at the end of a line about two thirds of the way down the page

- Letter 455A p. 267. In note 14, delete The Letters of John Addington Symonds

Vol. II.—The Less Important

- Letter 627A. p. 21. In note 7, Essays and Studies should be ES (1875)

- Letter 642B. p. 20. Note 1 should be deleted as redundant

- Letter 668A. p. 39. In note 2, delete Swinburne: Portrait of a Poet

- Letter 687A. p. 53. The letter from Swinburne that Powell mentions is untraced.

- Letter 728. p. 73. In note 5, delete the extraneous ()’s

- Letter 741A. p. 77. In note 5, expand “Hake and Compton-Rickett” to Thomas Hake and Arthur Compton Rickett, ed., The Letters of Algernon Charles Swinburne with Some Personal Recollections (London: John Murray, 1918).

- Letter 760A p. 88. In note 2, Essays and Studies should be ES (1875)

- Letter 836A. p. 117. Mourning Stationery should be mourning stationery

- Letter 847A. p. 123. In note 1, expand “Gooch and Thatcher” to Bryan N. S. Gooch and David S. Thatcher, Musical Settings of Late Victorian and Modern British Literature: A Catalogue (New York: Garland Pub., 1976).

- Letter 848A p. 124. In note 3, Maccoll should be MacColl

- Letter 874A. p. 132. In note 3, 8 August, 1877 should be 8 August 1877,

- Letter 880B. p. 134. In the head note, delete Mrs.

- Letter 889A. p. 140. In note 1, expand “Monckton Milnes” to Monckton Milnes: The Flight of Youth (London: Constable, 1949)

- Letter 913A. p. 149. In the head note, Swinburne should be , Swinburne

- Letter 944A. p. 168. In note 1, ‘ should be ’

- Letter 978F. p. 182. In note 3, artefacts should be artifacts

- Letter 978F. p. 183. In note 6, 1873 should be 1873,

- Letter 989C. p. 193. In note 8, Library should be Museum

- Letter 996A. p. 202. In the return address, ,S should be , S

- Letter 1001B. p. 206. In note 2, Letters should be see Letters

- Letter 1011E. p. 222. In note 3, or should be or,

- Letter 1032A. p. 234. In the text note, Library should be University

- Letter 1034A. p. 235. In the return address, Hill, should be Hill.

- Letter 1059A. p. 252. In note 1, Libraries should be Libraries,

- Letter 1077A. p. 264. The salutation is in the wrong font

- Letter 1081B. p. 268. In the PS, return . should be return.

- Letter 1110C. p. 276. In the text note, Fran-klin should be Frank-lin

- Letter 1205A. p. 321. In the text note, University should be University.

- Letter 1273A. p. 363. Expand “Life and Letters of Theodore Watts-Dunton” to Thomas Hake and Arthur Compton-Rickett, Life and Letters of Theodore Watts-Dunton, 2 vols. (London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1916).

- Letter 1273A. p. 364. In note 1, the title should be expanded to

Life and Letters of Benjamin Jowett, eds.

Evelyn AbbottandLewis Campbell, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1897).

- Letter 1295A. p. 372. In the head note, the should be The

- Letter 1312A. p. 375. In note 2, delete John Y.

- Letter 1322B. p. 380. In note 1, enclose the citation to The Times in ()’s

- Letter 1322C. p. 382. In note 3, CRC should be CR

- Letter 1393B p. 417. In note 2, p. 6 as should be p. 6, as

- Letter 1407C. p. 423. In the return address, The Pines should be centered above the date.

- Letter 1407D. p. 424. In the head note, [?] should be (?)

- Letter 1409A. p. 426. In note 1, 501). should be 501)).

- Letter 1526A. p. 485. In note 2, delete John Y.

Vol. III.—The Less Important

- Letter 1540B. p. 12. In note 1, below; should be below,

- Letter 1558A. p. 25. In the note, Spielman should be Spielmann

- Letter 1563B. p. 6. In note 3, delete A. C. Swinburne

- Letter 1601A. p. 41. In note 4, ,and should be , and

- Letter 1619B. p. 49. In text note, University should be University.

- Letter 1654C. p. 84. In note 22, 1894 should be 1894, above,

- Letter 1654C. p. 84. In note 22, 1895 should be 1895, below,

- Letter 1656C. p. 88. In note 1, delete George Eric Mackay

- Letter 1672A. p. 98. In note 1, delete the second sentence

- Letter 1679A. p. 99. In note 1, 1904) should be 1904))

- Letter 1695B. p. 110. In note 1, 7.45 should be 7:45

- Letter 1713A. p. 115. The date should be to the far left of the page

- Letter 1747A. p. 165. In note 1, delete the extra ) at the end

- Letter 1767A. p. 186. In the return address, Westcliffe-on-Sea, should be centered.

- Letter 1773D. p. 202. In note 5, Bookmen should be Bookman

- Letter 1774E. p. 213. Delete note 1 as redundant

- Letter 1774H. p. 217. The heading is in the wrong font and should be italicized and centered

- Letter 1779D. p. 223. In note 5, Autobiogaphical Notes should be expanded to William Bell Scott, Autobiographical Notes of the Life of William Bell Scott, ed. William Minto, 2 vols. (London: Osgood, McIlvaine 1892)

- Letter 1807A. p. 241. In the head note, Swinburne should be Swinburne,

- Letter 1809A. p. 248. In note 1, 257,A should be 257, A